Book Report: Heinrich Engel — The Japanese House: A Tradition for Contemporary Architecture

This certainly is the book I never completely read that I think about the most. It caught my eye because of its sheer size: the book weighs 2.6 kg! When I started browsing through its pages I was mesmerized. “The Japanese House” is a monumental opus containing the most fine-grained examination of Japanese architecture one could ever imagine.

“The Japanese House” is filled with pages upon pages of detailed drawings and plans of every aspect of a traditional Japanese house. However, it does not stop there — the book becomes an elaborate study of Japanese culture, society, and life. It looks into every facet that could possibly influence the way this traditional style of building came to be.

The author, Heinrich Engel In later editions referred to as Heino Engel, was a German architect. It is not easy to find information about him, though he has published several books, but this is what I could gather: Born in 1925 he studied architecture in Germany after the Second World War. In 1952 he left Germany and traveled through a number of eastern countries, before arriving in Japan. There he became fascinated with Japanese architecture and culture and stayed for three years, living with a Japanese family in Otsu. Later he taught at the University of Minnesota, returning to Offenbach, Germany, in 1964, where (from what I can tell) he spent the rest of his life until his death in 2013 I found an obituary which I suspect is about him, but I am not totally sure about this.. If I remember correctly — it has been a few years since I read the original — Engel started writing about Japanese architecture for his dissertation, which later became one of many chapters in the book. This might tell you something about the thoroughness of his writing.

The book was originally published in 1964 and after several reprints — in 1985 there had already been eleven — is unfortunately out of print today. There are some used copies to have, at wildly varying prices Depending on availability and condition prices start at 100€, but used copies also regularly go on Amazon for 800€.. I had only seen the original book at my university’s library, so I was happy when I found out that in 1985 the two chapters from the book that I care about the most had been singled out and published as a separate paperback book called “Measure and Construction of the Japanese House”, which is luckily readily available, in fact it was just republished in 2020. This release is much smaller than the original and does not quite do it justice, but given its price and availability, it is a more than decent surrogate. All page references given in the following are referring to this edition.

Length unit: Ken §

I was astonished by the fact that the Japanese language once had a specific word for a measurement unit which is not defined as an absolute value, but simply as a uniform length that defines the rhythm of a building:

In the latter half of Japan’s Middle Ages another length unit, the ken, appeared. Ken originally designated the interval between two columns of any wooden structure and varied in size.

Heino Engel in Measure and Construction of the Japanese House, p. 22

While “ken” quickly became standardized to mean a specific measurement 6 shaku or about 1.82 meters it still amazes me that a culture could have a length unit for such an abstract property of design.

The Kyo-Ma Method and the Inaka-Ma Method §

Every designer knows the challenge of setting up a grid and being confronted with the decision whether the spacing between the content of the columns (or rows), usually referred to as “gutter”, is sitting between the columns or is considered to be part of the columns themselves. I have been switching between both methods depending on the project (and sometimes later regretted the decision I made), so I felt validated when I learned that the same discussion has been common in Japanese architecture for centuries, where a grid of tatami mats defines the grid of buildings. Engel points out that this description isn’t entirely accurate: The size of the mats was influenced by the ken-based grid of the building, but this, in turn, led to the grid being solidified, and room sizes being given in mats. Is the wall part of the mats, or placed between?

Over time two different methods of design have been established: the “kyo-ma”, where the columns are spaced according to the width of the mats, which results in different distances between the columns for with the same amount of mats in between; and the “inaka-ma” method, where all columns are placed on a strict grid, which results in multiple sizes of mats.

Historically speaking, the kyo-ma method was primarily used within cities (“kyo-ma ken” literally means “column distance in metropolis measurement”) while the inaka-ma method was used in the countryside (“inaka-ma ken” literally means “column distance in countryside measurement”). This distinction quickly vanished however and the methods became used consistently in more general regions.

The kyo-ma method of course comes with the problem that the width of rooms which span multiple “columns” are not exact multiples of the width of the smaller rooms, which span only one “column” (see the right side of the illustration ). This means you have to fill the larger rooms with additional wooden flooring on the sides. According to Engel, it is the method that is predominantly used regardless.

While the inaka-ma method is more consistent, it comes with a different set of problems. Because the walls are measured as part of the rooms, the rooms become smaller. This problem is intensified by the fact that a inaka-ma ken already is smaller than a kyo-ma ken, which measures 6.5 shaku. The distance between two columns might become so narrow, that in the case of very small rooms like hallways the grid is ignored and the width is defined as an irregular measurement (i.e. 1.5 ken).

From the viewpoint of contemporary architecture with its standardization, such conscious tolerance toward self-imposed order is significant. For it shows that even the most unique standardization that architecture has produced still does not completely fulfill all the demands of structure, function, economy, and aesthetics.

Heino Engel in Measure and Construction of the Japanese House, p. 39

Interestingly Engel points out that both methods only work because the building of houses is not industrialized but handicraft. The craftsmen can adapt and react to deviations, which are unavoidable. This reminds me of a similar conflict — that of spacing the triglyphs in the Doric order in ancient Greek architecture.

Superstition §

Engel describes that the plan for a traditional Japanese house, at least at the time of his writing in the sixties, would usually be checked by a professional soothsayer before construction started, to make sure that “the orientation of rooms, the location of important features of the house, and the organization of the total site would not be in contrast to the mysterious instructions handed down from the past.” (p. 53) There is a system based on the points of the compass (with 24 distinct directions), each of which is assigned a certain spirit or meaning, according to which elements of the house should be placed. A toilet shouldn’t be placed in the northeast–southeast axis, but a garden hill in the northeast will bring good luck and ward off demons, and so on. The system isn’t rigid and has to be checked on a case-by-case basis.

Engel claims that because the observance of the rules is based on “fear of the unknown and […] belief in magic, the rules must properly be called superstitious.” The most interesting point, however, is that he does point out that most of the rules do make sense from an architectural point of view and are probably originally based on observations of the local climate: “although the instructions contain gross and inexplicable contradictions and may obstruct the exploitation of a good design idea, there are many of them that do make sense, especially with regard to the climate. The climatic implication is also evident in the dependence of these rules on the cardinal points of the compass, and, indeed, if considered from the viewpoint of sun exposure, wind direction, bad weatherside, etc., the rules seem to be quite reasonable and helpful.” (p. 57) He points out that they do work well as rules of thumb when designing a house and will help avoid many errors: “Thus, it rightly can be assumed that the basis of these superstitious rules is the concern with the health of the inhabitants. Their purpose is to give the ‘designers’ of the house a handy rule of thumb, the observance of which would avoid errors in design; and the carpenter manuals suggest that in designing a house, though one need not strictly follow these rules, one should by no means ignore them.” (p. 58) This reminds me of an argument made by Nassim Nicholas Taleb in “Antifragile” that we shouldn’t discount knowledge and traditions that have been around for a long time, even if they seem incomprehensible, useless, or even outright wrong because them being around for so long indicates that they must have some merit, even if it isn’t exactly the one they claim to have. I am wary of this argument, which results in extreme conservatism because there have been at least as many beliefs that persisted for centuries, which turned out to be disastrously wrong and harmful.

Critique of the Japanese House §

While Engel’s admiration for Japanese architecture is beyond doubt and his deference becomes clear through the granularity and depth of his analysis and descriptions — throughout the book he often points out misconceptions about Japanese architecture in western literature —, he does not shy away from critique.

Because the design of the house has been considered to already be brought to perfection, it has remained unchanged for centuries. Carpenters do not dare to even try and come up with improvements to the standards, because changing them would go against their professional beliefs and would be considered sacrilegious: “Throughout centuries, therefore, method and construction have remained stagnant at a primitive stage and have essentially strangled progress in building and living. Thus the present residence constitutes a strange contrast of primitivity in essence and perfection in performance. In this instance, the Japanese house clearly demonstrates a defective tendency caused by standardization.” (p. 29)

Perfection & Stagnation §

This stagnation has resulted in a lack of innovation which means that the house has become out of touch with the needs of the present: “[…] the real crux of the matter is that this house has meant a realistic architectural solution only for the society of the past. Except for inherited basic constructional defects, the Japanese house had reached a level of perfection that did not demand improvement if considered from the standpoint of living modes and requirements of the past. However, the word ‘perfection’ implies not only the quality of being superb, but also the state of being completed and finished; and indeed the development of Japanese residential architecture has long since come to a standstill; its culmination is over. New technical impediments such as electricity, furniture, glass, metal, radio, etc. adopted from the West have degraded the quality and standard of the traditional Japanese residence; gradual Westernization of living manners has rendered inadequate what formerly was spatially convenient; and dissolution of the traditional family system has removed the philosophical basis that underlies the Japanese house.” (p. 33)

I know very little about contemporary Japanese architecture, but based on what I learned about Tadao Ando’s work and his calls to re-establish traditional ideas and patterns in modern architecture, it seems that the conflict that Engel described has in the meantime led to a strong Westernization of Japanese architecture, which only recently has reoriented itself to take more pride in its rich history.

Primitiveness & Sophistication §

Engel observes “a strange contrast” in the traditional Japanese house, between the highly sophisticated work in detail, and the very primitive structural framework that it is based on.

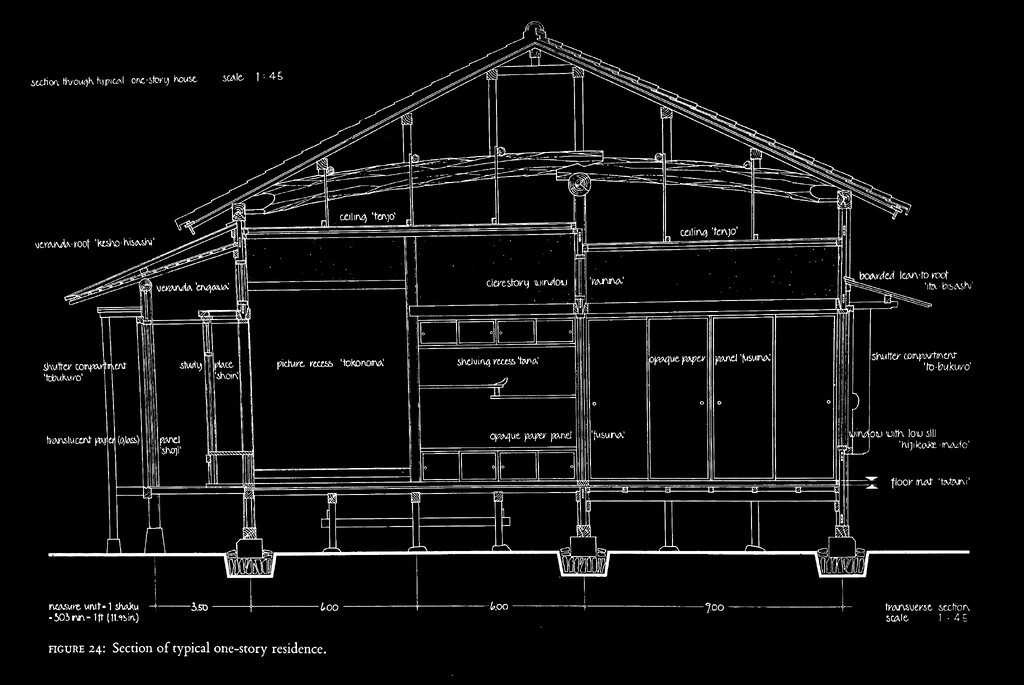

The framework does not use any braces and diagonals, only horizontal and vertical beams. Even the roof, which is exceptionally heavy because is covered in clay, does not use a triangular construction, but rather directs all stress directly downwards onto a single horizontal beam that spans the entire width of the house (Fig. 4). Because of this method of construction, the entire framework is very ill-adapted to withstand horizontal stress — which seems rather strange in a country that is prone to extreme weather events and earthquakes.

On the other hand, Japan is famous for its extremely sophisticated carpentry and the hundreds of different, highly complex joints that are used in construction. While at first sight, this may seem in conflict with the primitive structural construction, Engel points out that it isn’t: “And it is no contradiction […] that in detail Japanese construction displays high elaborateness and a refinement that has reached perfection in method, economy, and form. […] Indeed, it appears that the very reason for Japan’s famous refinement in constructional detail was the immutability of the basic constructional system which directed the handicraftsman’s imaginative spirit to detail and provided centuries for gradual empirical improvement. While primitiveness of structural system might at first sight appear contradictory to the refinement of constructional detail, it becomes evident that one was only the logical consequence of the other.” (p. 71)

The great advantage of the simple framework and roof is that many parts can be prefabricated and then put up in a matter of days, providing a protected space for all further work: “The roof, then, is the first component of the Japanese residence to be completed in the construction process, and it appears as if the preceding work is primarily orientated to achieve that aim in the quickest way possible. Once material and man is protected against the frequent rains, the carpenter can continue his work with more ease and leisure. This change of pace seems to be almost symbolic of the distinct difference in constructional quality, for the succeeding work displays high elaborateness, structural sense, and sophisticated refinement […]” (p. 76)

Structure of Content §

One of my favorite aspects of the book is how the content is structured because it represents the immense number of aspects that a design is influenced by: Chapters 1.2 and 1.4 are the ones singled out in the smaller volume.

- Structure

- Fabric

- Measure

- Design

- Construction

- Organism

- Family

- Space

- Garden

- Seclusion

- Environment

- Geo-Relationship

- Climate

- Philosophy

- Society

- Aesthetics

- Taste

- Order

- Expression

Structure of Content (unabridged) §

For reference, this is the table of contents in its entirety:

- Structure

- Fabric

- definiton

- stone

- glass

- bamboo

- clay

- paper

- roof tiles

- floor mat

- wood

- for contemporary architecture

- Measure

- defintion

- building measures

- early measures and shaku

- ken measure and module

- order of kiwaki

- traditional standards

- for contemporary architecture

- Design

- definition

- kyo-ma method

- inaka-ma method

- process of design

- present building regulations

- distinction

- superstition

- for contemporary architecture

- Construction

- definition

- process

- foundations

- wall framework

- roof

- Japanese wall

- floor

- ceiling

- fitting

- translucent paper panel

- opaque paper panel

- windows

- picture recess

- shelving recess

- study place

- wooden shutters

- shutter compartment

- doors

- for contemporary architecture

- Fabric

- Organism

- Family

- definition

- moral principles

- manners of living

- influence on house

- influence from house

- for contemporary architecture

- Space

- defintion

- measure of man

- planmetric-functional space

- space relationship

- physique of space

- for contemporary architecture

- Garden

- defition

- attitude towards nature

- house-garden relationship

- standardization

- standard features

- for contemporary architecture

- Seclusion

- definition

- necessity of tea

- philosophy of tea

- physique of the tearoom

- art of living

- tea garden

- standardization

- for contemporary architecture

- Family

- Environment

- Geo-Relationship

- defintion

- racial migration

- closeness to the continent

- insular isolation

- imitation

- for contemporary architecture

- Climate

- definition

- characteristics

- earthquakes

- climatic architecture

- climatic adaption

- for contemporary architecture

- Philosophy

- definition

- zen-buddhism

- buddhist features

- religious expression

- zen and house

- for contemporary architecture

- Society

- defintion

- policy

- social order

- city community

- prohibition

- for contemporary architecture

- Geo-Relationship

- Aesthetics

- Taste

- defintion

- theory of genesis

- zen aestheticism

- traditional trait

- taste of the townspeople

- for contemporary architecture

- Order

- definition

- theory of genesis

- physical order

- spiritual order

- for contemporary architecture

- Expression

- defintion

- interior

- contrast

- individuality

- association

- exterior

- for contemporary architecture

- Taste

Continue Reading All Notes

-

UnfinishedNotes from Glenn Parsons’ The Philosophy of Design

-

30. September 2023Travel Notes: Medellín

-

06. July 2023Travel Notes: Grottole